As of 2011, NPIC stopped creating technical pesticide fact sheets. The old collection of technical fact sheets will remain available in this archive, but they may contain out-of-date material. NPIC no longer has the capacity to consistently update them. To visit our general fact sheets, click here. For up-to-date technical fact sheets, please visit the Environmental Protection Agency’s webpage.

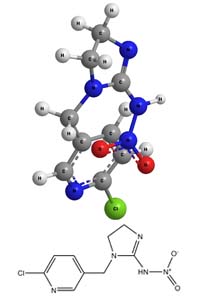

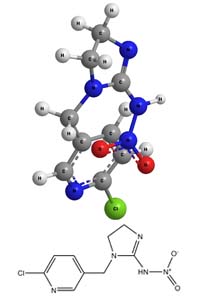

Molecular Structure -

Imidacloprid

Laboratory Testing: Before pesticides are registered by

the U.S. EPA, they must undergo laboratory testing for

short-term (acute) and long-term (chronic) health effects.

Laboratory animals are purposely given high enough doses

to cause toxic effects. These tests help scientists judge how

these chemicals might affect humans, domestic animals,

and wildlife in cases of overexposure.

- Imidacloprid is a neonicotinoid insecticide in the chloronicotinyl

nitroguanidine chemical family.1,2 The International Union

of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) name is 1-(6-chloro-3-

pyridylmethyl)-N-nitroimidazolidin-2-ylideneamine and the

Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry number is 138261-41-3.2

- Neonicotinoid insecticides are synthetic derivatives of nicotine, an alkaloid compound found in the leaves of many plants

in addition to tobacco.3,4,5

- Imidacloprid was first registered for use in the U.S. by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) in

1994.6 See the text box on Laboratory Testing.

- Imidacloprid is made up of colorless crystals with a slight but characteristic

odor.2

- Vapor pressure7: 3 x 10-12 mmHg at 20 °C

- Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient (Kow)2: 0.57 at 21 °C

- Henry's constant2: 1.7 x 10-10 Pa·m3/mol

- Molecular weight2: 255.7 g/mol

- Solubility (water)2: 0.61 g/L (610 mg/L) at 20 °C

- Soil Sorption Coefficient (Koc)8,9: 156-960, mean values 249-336

- Imidacloprid is used to control sucking insects, some chewing insects including

termites, soil insects, and fleas on pets. In addition to its topical use on pets, imidacloprid

may be applied to structures, crops, soil, and as a seed treatment.2,10

Uses for individual products containing imidacloprid vary widely. Always read

and follow the label when applying pesticide products.

- Signal words for products containing imidacloprid may range from Caution to Danger. The signal word reflects the combined

toxicity of the active ingredient and other ingredients in the product. See the pesticide label on the product and refer to

the NPIC fact sheets on Signal Words and Inert or "Other" Ingredients.

- To find a list of products containing imidacloprid which are registered in your state, visit the website

https://npic.orst.edu/reg/state_agencies.html select your state then click on the link for "State Products."

Target Organisms

- Imidacloprid is designed to be effective by contact or ingestion.2 It is a systemic insecticide that translocates rapidly through

plant tissues following application.2,10

- Imidacloprid acts on several types of post-synaptic nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nervous system.11,12 In insects,

these receptors are located only within the central nervous system. Following binding to the nicotinic receptor, nerve

impulses are spontaneously discharged at first, followed by failure of the neuron to propagate any signal.13,14 Sustained

activation of the receptor results from the inability of acetylcholinesterases to break down the pesticide.12 This binding

process is irreversible.5

Non-target Organisms

- Imidacloprid's mode of action is similar on target and non-target beneficial insects including honeybees, predatory ground

beetles and parasitoid wasps.10 However, imidacloprid is ineffective against spider mites and nematodes.2

- Mammalian nicotinic receptors are made up of a number of subtypes.14 In contrast to insects, these receptors are present

at neuromuscular junctions as well as in the central nervous system.14 However, the binding affinity of imidacloprid at the

nicotinic receptors in mammals is much less than that of insect nicotinic receptors.15 This appears to be true of other vertebrate

groups including birds.16,17

- The blood-brain barrier in vertebrates blocks access of imidacloprid to the central nervous system, reducing its toxicity.14

Oral

- Imidacloprid is moderately toxic if ingested.18 Oral LD50 values in

rats were estimated to be 450 mg/kg for both sexes in one study

and 500 and 380 mg/kg in males and females, respectively in

another study.2,19 In mice, LD50 values were estimated at 130 mg/kg for males and 170 mg/kg for females.19,20 See the text boxes

on Toxicity Classification and LD50/LC50.

LD50/LC50: A common

measure of acute toxicity is the lethal dose (LD50) or

lethal concentration (LC50) that causes death (resulting

from a single or limited exposure) in 50 percent of the treated

animals. LD50 is generally expressed as the dose in

milligrams (mg) of chemical per kilogram (kg) of body

weight. LC50 is often expressed as mg of chemical per

volume (e.g., liter (L)) of medium (i.e., air or water) the organism

is exposed to. Chemicals are considered highly toxic when the

LD50/LC50 is small and practically non-toxic

when the value is large. However, the LD50/LC50

does not reflect any effects from long-term exposure (i.e., cancer,

birth defects or reproductive toxicity) that may occur at levels below

those that cause death.

Dermal

- Imidacloprid is very low in toxicity via dermal exposure.18 The

dermal LD50 in rats was estimated at greater than 5000 mg/kg.2,19

- Researchers did not observe eye or skin irritation in rabbits.19,20 Imidacloprid is not considered a skin sensitizer20 although

reports of hypersensitivity in skin following exposure to imidacloprid have been reported in companion animals.1

Inhalation

- Imidacloprid is variable in toxicity if inhaled. The inhalation LC50 was estimated to be greater than 5323 mg/m3 for dust

and 69 mg/m3 for aerosol exposure in rats.2,20 Imidacloprid dust is considered slightly toxic but the aerosol form is highly

toxic.18

| TOXICITY CLASSIFICATION - IMIDACLOPRID |

|

High Toxicity |

Moderate Toxicity |

Low Toxicity |

Very Low Toxicity |

| Acute Oral LD50 |

Up to and including 50 mg/kg

(≤ 50 mg/kg) |

Greater than 50 through 500 mg/kg

(>50-500 mg/kg) |

Greater than 500 through 5000 mg/kg

(>500-5000 mg/kg) |

Greater than 5000 mg/kg

(>5000 mg/kg) |

| Inhalation LC50 |

Up to and including 0.05 mg/L

(≤0.05 mg/L) |

Greater than 0.05 through 0.5 mg/L

(>0.05-0.5 mg/L) |

Greater than 0.5 through 2.0 mg/L

(>0.5-2.0 mg/L) |

Greater than 2.0 mg/L

(>2.0 mg/L) |

| Dermal LD50 |

Up to and including 200 mg/kg

(≤200 mg/kg) |

Greater than 200 through 2000 mg/kg

(>200-2000 mg/kg) |

Greater than 2000 through 5000 mg/kg

(>2000-5000 mg/kg) |

Greater than 5000 mg/kg

(>5000 mg/kg) |

| Primary Eye Irritation |

Corrosive (irreversible destruction of

ocular tissue) or corneal involvement or

irritation persisting for more than 21 days |

Corneal involvement or other

eye irritation clearing in 8 - 21 days |

Corneal involvement or other

eye irritation clearing in 7

days or less |

Minimal effects clearing in less than 24 hours |

| Primary Skin Irritation |

Corrosive (tissue destruction into the

dermis and/or scarring) |

Severe irritation at 72 hours

(severe erythema or edema) |

Moderate irritation at 72

hours (moderate erythema) |

Mild or slight irritation at

72 hours (no irritation or

erythema) |

| The highlighted boxes reflect the values in the "Acute Toxicity" section of this fact sheet. Modeled after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pesticide Programs, Label Review Manual, Chapter 7: Precautionary Labeling. https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2018-04/documents/chap-07-mar-2018.pdf |

Signs of Toxicity - Animals

- Salivation and vomiting have been reported following oral exposure.1,6 Very high oral exposures may lead to lethargy,

vomiting, diarrhea, salivation, muscle weakness and ataxia, which are all indicative of imidacloprid's action on nicotinic

receptors.1 Other signs of exposure at high doses are uncoordinated gait, tremors, and reduced activity.20

- Hypersensitivity reactions in skin have been reported following dermal applications of products containing imidacloprid.1

- Onset of signs of toxicity is rapid following acute exposure. In rats, clinical signs of intoxication occurred within 15 minutes

of oral exposure.14,21 Signs of toxicity disappear rapidly, with most resolving within 24 hours of the exposure. Lacrimation

and urine staining may persist for up to four days after exposure to some neonicotinoids. Death occurred within 24 hours

following administration of lethal doses.21

- Neither persistent neurotoxic effects nor effects with a delayed onset have been reported for imidacloprid.21

Signs of Toxicity - Humans

- Three case reports of attempted suicides described signs of toxicity including drowsiness, dizziness, vomiting, disorientation,

and fever.22,23,24 In two of these cases, the authors concluded that the other ingredients in the formulated product

ingested by the victims were more likely to account for many of the observed signs.22,23

- A 69-year-old woman ingested a formulated product containing 9.6% imidacloprid in N-methyl pyrrolide solution. The

woman suffered severe cardiac toxicity and death 12 hours after the exposure.25 Signs of toxicity soon after the ingestion

included disorientation, sweating, vomiting, and increased heart and respiratory rates.25

- A 24-year-old man who accidentally inhaled a pesticide containing 17.8% imidacloprid while working on his farm was

disoriented, agitated, incoherent, sweating and breathless following the exposure.26

- Pet owners have reported contact dermatitis following the use of veterinary products containing imidacloprid on their

pets.19

- Always follow label instructions and take steps to minimize exposure. If any exposure occurs, be sure to follow the First Aid

instructions on the product label carefully. For additional treatment advice, contact the Poison Control Center at 1-800-

222-1222. If you wish to discuss an incident with the National Pesticide Information Center, please call 1-800-858-7378.

Animals

- Rats consumed imidacloprid in their diet for three months at doses

of 14, 61, and 300 mg/kg/day for males and 20, 83, and 420 mg/

kg/day for females. Researchers noted reductions in body weight

gain, liver damage, and reduced blood clotting function and platelet

counts at 61 mg/kg/day in males and 420 mg/kg/day in females.

Liver damage disappeared after exposure ended, but abnormalities

in the blood were not entirely reversible. Researchers estimated

the NOAEL at 14 mg/kg/day.27 See the text box on NOAEL, NOEL,LOAEL, and LOEL.

NOAEL: No Observable Adverse Effect Level

NOEL: No Observed Effect Level

LOAEL: Lowest Observable Adverse Effect Level

LOEL: Lowest Observed Effect Level

- Imidacloprid dust was administered through the noses of rats for six hours a day, five days a week for four weeks at concentrations

of 5.5, 30.0, and 190.0 mg/m3. Male rats exhibited reduced body weight gain at the two highest doses and at

the highest dose, increased liver enzyme activity and increased blood coagulation time was noted. Female rats exhibited

increased liver enzyme activity at the two highest doses and at the highest dose, researchers noted enlarged livers and

reduced thrombocyte counts. No effects were observed at the lowest dose.28

- Researchers applied a paste containing 1000 mg/kg imidacloprid to the shaved flanks and backs of rabbits, exposing the

rabbits for 6 hours a day for 15 days. Rabbits showed no effects from the treatment.29

- Researchers fed imidacloprid to beagles for one year. Concentrations were 200, 500, or 1250 ppm for the first 16 weeks

and 200, 500, and 2500 ppm for the remainder of the trial. Doses were equivalent to 6.1, 15.0, and 41.0 or 72.0 mg/kg/day.

Researchers noted reduced food intake in the highest dose group. Females in this group exhibited increased plasma cholesterol

concentrations at 13 and 26 weeks. Both males and females in this group exhibited increased cytochrome P450

activity in the liver and increases in liver weights at the end of the study. No adverse effects were observed at the two lowest

doses.30

Humans

- No studies were found involving human subjects chronically exposed to imidacloprid. See the text box on Exposure.

Exposure: Effects of imidacloprid on human health and the environment depend on how much

imidacloprid is present and the length and frequency of exposure. Effects also depend on the health

of a person and/or certain environmental factors.

- The chronic dietary reference dose (RfD) has been set at 0.057 mg/kg/day based on chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity

studies using rats. The NOAEL was estimated to be 5.7 mg/kg/day and the LOAEL was set at 16.9 mg/kg/day based on increased

occurrence of mineralized particles in the thyroid gland of male rats.31 See the text box on Reference Dose (RfD).

- No data were found evaluating the potential of imidacloprid to disrupt endocrine function.

- Imidacloprid is included in the draft list of initial chemicals for screening under the U.S. EPA Endocrine Disruptor Screening

Program (EDSP).32 The list of chemicals was generated based on exposure potential, not based on whether the pesticide is

a known or likely potential endocrine disruptor.

Animals

- Researchers concluded that Scottish terriers treated with topical flea and tick products, including those containing imidacloprid,

did not have a greater risk of developing urinary bladder cancer compared with control dogs.33 Rats were fed imidacloprid

for 18 or 24 months at unspecified concentrations. Although signs of toxicity were noted, researchers concluded

that imidacloprid showed no evidence of carcinogenic potential.20

- A range of studies using both in vitro and in vivo techniques concluded that imidacloprid did not damage DNA.19

Humans

- The U.S. EPA has classified imidacloprid into Group E, no evidence of carcinogenicity, based on studies with rats and mice.20,31

See the text box on Cancer.

Cancer: Government agencies in the United States and abroad have developed programs to evaluate the

potential for a chemical to cause cancer. Testing guidelines and classification systems vary. To learn more

about the meaning of various cancer classification descriptors listed in this fact sheet, please visit the

appropriate reference, or call NPIC.

- Imidacloprid has not been evaluated for the carcinogenicity by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), nor

the National Toxicology Program (NTP).

- A study of human lymphocytes exposed to greater than 5200 μg/mL of imidacloprid demonstrated a slight increase in

chromosome abnormalities in vitro, but this result was not found with in vivo tests.19

Animals

- Rats were fed imidacloprid at doses of 10, 30, or 100 mg/kg/day on days 6 to 15 of their pregnancies.20 On day 21 of the

pregnancy, rats at the highest doses showed reduced embryo development and signs of maternal toxicity. In addition,

wavy ribs were observed in the fetuses.20,34

- Researchers fed rabbits doses of imidacloprid at 8, 24, or 72 mg/kg/day during days 6-18 of pregnancy. On day 28 of pregnancy,

researches noted maternal toxicity including death in the highest dose group, and the animals that survived in

this group carried embryos with reduced rates of growth and bone ossification. In some of these rabbits, the young were

aborted or resorbed.20,35

- In a two-generation study of reproductive toxicity, researchers dosed rats with 100, 250, or 700 ppm of imidacloprid in their

diet for 87 days until rats mated. This was equivalent to 6.6, 17.0, and 47.0 mg/kg/day. Mother rats exhibited increased Odemethylase

activity at doses of 17 mg/kg/day and greater. Reduced body weight gains were noted in pups at doses of 47 mg/kg/day. No effects on reproductive behavior or success were observed.20,36

Humans

- No human data were found on the reproductive effects of imidacloprid.

Absorption

- The gastrointestinal tract of rats absorbed 92% of an unspecified dose. Plasma concentrations peaked 2.5 hours after administration.19

- Little systemic absorption through the skin occurs following dermal exposure in pets.1

- Researchers tested imidacloprid absorption using human intestinal cells. Cells rapidly absorbed imidacloprid at a very high

rate of efficiency. Researchers concluded that an active transport system was involved.37

Distribution

- Researchers administered a single oral dose of radio-labeled imidacloprid at 20 mg/kg to male rats. One hour after dosing,

imidacloprid was detected throughout the bodies with the exception of fatty tissues and the central nervous system.38

- No studies were found examining the distribution of imidacloprid in humans.

Metabolism

- Mammals metabolize imidacloprid in two major pathways discussed below. Metabolism occurs primarily in the liver.20

- In the first pathway, imidacloprid may be broken by oxidative cleavage to 6-chloronicotinic acid and imidazolidine. Imidazolidine

is excreted in the urine, and 6-chloronicotinic acid undergoes further metabolism via glutathione conjugation to

form mercaptonicotinic acid and a hippuric acid.20,39

- Imidacloprid may also be metabolized by hydroxylation of the imidazolidine ring in the second major pathway.20,39 Metabolic

products from the second pathway include 5-hydroxy and olefin derivatives.40

Excretion

- The metabolic products 5-hydroxy and olefin derivatives resulting from hydroxylation of the imidazolidine ring are excreted

in both the feces and urine.39,41

- Metabolites found in urine include 6-chloronicotinic acid and its glycine conjugate, and accounted for roughly 20% of the

original radio-labeled dose.42

- Metabolites in the feces accounted for roughly 80% of the administered dose in rats and included monohydroxylated

derivatives in addition to unmetabolized imidacloprid, which made up roughly 15% of the total. Olefin, guanidine, and the

glycine conjugate of methylthionicotinic acid were identified as minor metabolites.2,42

- Rats excreted 96% of radio-labeled imidacloprid within 48 hours following an unspecified oral dosing, with 90% excreted

in the first 24 hours.40 Radio-labeled imidacloprid was present in low amounts in organs and tissues 24 hours after male rats

were orally dosed with 20 mg/kg.38

- No information was found on the specific metabolism of imidacloprid in humans.

- Researchers have tested for imidacloprid exposure in farm workers

by evaluating urine samples with high performance liquid chromatography.43

The method has not been well studied in humans and the

clinical significance of detected residues is unknown.

The "half-life" is the time required for half of the

compound to break down in the environment.

1 half-life = 50% remaining

2 half-lives = 25% remaining

3 half-lives = 12% remaining

4 half-lives = 6% remaining

5 half-lives = 3% remaining

Half-lives can vary widely based on environmental

factors. The amount of chemical remaining after a

half-life will always depend on the amount of the

chemical originally applied. It should be noted that

some chemicals may degrade into compounds of

toxicological significance.

Soil

- Soil half-life for imidacloprid ranged from 40 days in unamended soil

to up to 124 days for soil recently amended with organic fertilizers.44

See the text box on Half-life.

- Researchers incubated three sandy loams and a silt loam in darkness

following application of [14C-methylene]-imidacloprid for a year. The degradation time required for imidacloprid to break down to half its initial concentration (DT50) in non-agricultural soil

was estimated to be 188-997 days. In cropped soils, the DT50 was estimated to be 69 days.42 Metabolites found in the soil

samples included 6-chloronicotinic acid, two cyclic ureas, olefinic cyclic nitroguanidine, a cyclic guanidine, and its nitroso

and nitro derivatives. After 100 days, metabolites each accounted for less than 2% of the radiocarbon label.42

- Sorption of imidacloprid to soil generally increases with soil organic matter content.45,46 However, researchers have demonstrated

that sorption tendency also depends on imidacloprid concentration in the soil. Sorption is decreased at high soil

concentrations of imidacloprid. As imidacloprid moves away from the area of high concentration, sorption again increases,

limiting further movement.46

- Imidacloprid's binding to soil also decreases in the presence of dissolved organic carbon in calcareous soil. The mechanism

may be through either competition between the dissolved organic carbon and the imidacloprid for sorption sites in the

soil or from interactions between imidacloprid and the organic carbon in solution. Such interactions suggest that the potential

for imidacloprid to leach into ground water would increase in the presence of dissolved organic carbon.47

- Researchers found no imidacloprid residue in soil 10-20 cm under or around sugar beets grown from treated seeds, and

concluded that no leaching had occurred.48

- Metabolites found in agricultural soils used for growing sugar beets from imidacloprid-treated seed included 6-hydroxynicotinic

acid, (1-[(6-chloro-3-pyridinyl)methul]-2-imidazolidone), 6-chloronicotinic acid, with lesser amounts of a fourth

compound, 2-imidazolidone.48

- In another laboratory study of soil and imidacloprid, researchers determined that half lives varied by both product formulation

and soil type. Metabolites were first detected 15 days after imidacloprid was applied.49

- Imidacloprid residues became increasingly bound to soil with time, and by the end of the one year test period, up to 40%

of the radio-label could not be extracted from the soil samples.42

- In a water-sediment system, imidacloprid was degraded by microbes to a guanidine compound. The time to disappearance

of one-half of the residues (DT50) was 30-162 days.42

- Photodegradation at the surface of a sandy loam soil was rapid at first in a laboratory test, with a measured DT50 of 4.7

days, but the rate slowed after that time. Metabolites included 5-hydroxy-imidacloprid, which was the major product, and

lesser amounts of an olefin, nitroso derivative, a cyclic urea, and 6-chloronicotinic acid in addition to two unidentified

products.42

Water

- Imidacloprid is broken down in water by photolysis.45 Imidacloprid is stable to hydrolysis in acidic or neutral conditions, but

hydrolysis increases with increasing alkaline pH and temperature.50

- Researchers determined that hydrolysis of imidacloprid produced the metabolite 1-[(6-chloro-3-pridinyl)methyl]-2-imidazolidone.50

This may be further broken down via oxidative cleavage of the N-C bond between the pyridine and imidazolidine

rings, and the resulting compounds may be broken down into C02, N03-, and Cl-.45

- When imidacloprid was added to water at pH 7 and irradiated with a xenon lamp, half of the imidacloprid was photolyzed

within 57 minutes.42 Nine metabolites were identified in the water, of which five were most prominent. These included a

cyclic guanidine derivative, a cyclic urea, an olefinic cyclic guanidine, and two fused ring products. These metabolites accounted

for 48% of the radio carbon label following two hours of radiation, and the parent compound accounted for 23%

of the label.42

- Although hydrolysis and photodegradation proceeded along different metabolic pathways in aqueous solution, the main

metabolite was imidacloprid-urea in both cases.45

- At pH 7, only 1.5% of the initial concentration of 20 mg/L of imidacloprid was lost due to hydrolysis in three months, whereas

at pH 9, 20% had been hydrolyzed in samples that were kept in darkness for the same time period.50

- The presence of dissolved organic carbon in calcareous soil may decrease the sorption potential of imidacloprid to soil, and

thus increase the potential for imidacloprid to leach and contaminate groundwater.47

- A total of 28.7% of imidacloprid applied to a 25 cm soil column in the laboratory was recovered in leachate. Formulated

products showed greater rates of leaching likely due to the effects of carriers and surfactants. Under natural conditions, soil

compaction and rainfall amount may also affect leaching potential.51

- Imidacloprid is not expected to volatilize from water.7

Air

- Volatilization potential is low due to imidacloprid's low vapor pressure.7

- Imidacloprid is metabolized by photodegradation from soil surfaces and water.42

Plants

- Imidacloprid applied to soil is taken up by plant roots and translocated throughout the plant tissues.2 Freshly cut sugar

beet leaves contained 1 mg/kg imidacloprid residues up to 80 days following sowing of treated seed although residues

were undetectable at harvest 113 days after sowing.44 In a similar study, sugar beet leaves harvested 21 days after the sowing

of treated seeds contained an average of 15.2 μg/g imidacloprid.52

- Researchers grew tomato plants in soil treated with 0.333 mg active ingredient per test pot, and monitored the plants and

fruits for 75 days. Plants absorbed a total of 7.9% of the imidacloprid over the course of the experiment, although absorption

of imidacloprid declined with time since application.53

- More than 85% of the imidacloprid taken up by the tomato plants was translocated to the shoots, and only small quantities

were found in the roots. Shoot concentrations declined towards the top of the plant. These patterns were also seen in sugar

beets grown from treated seed.52 The tomato fruits also contained imidacloprid, although tissue concentrations were not

related to the position of the fruits on the plant.53

- Although tomato fruits contained primarily unmetabolized imidacloprid, the plants' leaves also included small quantities

of the guanidine metabolite, a tentatively identified olefin metabolite, and an unidentified polar metabolite in addition to

the parent compound.53 However, sugar beets grown from treated seed appeared to rapidly metabolize imidacloprid in

the leaves. On day 97 after sowing, the majority of the radio-label was associated with metabolites, not the parent compound.52

- Researchers sprayed imidacloprid on eggplant, cabbage, and mustard crops at rates of 20 and 40 g/ha when the crops

were at 50% fruit formation, curd formation, and pod formation, respectively.54 The researchers calculated foliar half-lives

of 3 to 5 days based on the measured residues.54

- Metabolites detected in the eggplant, cabbage, and mustard plants included the urea derivative [1-(6-chloropyridin-3-

ylmethil)imidazolidin-2-one] and 6-chloronicotinic acid 10 days after foliar application. Residues of 2.15-3.34 μg/g were

detected in the eggplant fruit.54

- Three plant metabolites of imidacloprid, the imidazolidine derivative, the olefin metabolite and the nitroso-derivative, were

more toxic to aphids than imidacloprid itself.55

Indoor

- No information regarding indoor half-life or residues was found for imidacloprid.

- Researchers measured residue transfer of a commercial spot-on product containing imidacloprid on dogs'

fur to people. Gloves worn to pat the dogs contained an average of 254 ppm of imidacloprid 24 hours following application

of the product. Residues from the fur declined to an average of 4.96 ppm by the end of the first week.56

Food Residue

- The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Pesticide Data Program monitored imidacloprid residues in food

and published their findings in 2006. Imidacloprid was detected in a range of fresh and processed fruits and vegetables. It

was detected in over 80% of all bananas tested, 76% of cauliflower, and 72% of spinach samples. In all cases, however, the

levels detected were below the U.S. EPA's tolerance levels. Imidacloprid was also found in 17.5 % of applesauce and 0.9%

raisin samples, although percentage of detections were greater in the fresh unprocessed fruit (26.6% of apples sampled,

and 18.1% of grapes sampled).57

- Imidacloprid was not one of the compounds sampled for the 2006 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Food

Safety and Applied Nutrition's Pesticide Residue Monitoring Program.57

Birds

- The acute LD50 for birds varies by species; it was determined to be 31 mg/kg in Japanese quail but 152 mg/kg in bobwhite

quail. However, dietary LC50 values for a five-day interval were 2225 mg/kg/day for bobwhite quail and in excess of 5000

mg/kg for mallard ducks.2

Fish and Aquatic Life

- LC50 values for a 96-hour exposure were 237 mg/L for golden orfe (Leuciscus idus) and 21 mg/L for rainbow trout (Oncorhyncus

mykiss).2

- Researchers determined LC50 values of 85 mg/L for Daphnia with a 48-hour exposure. A concentration of greater than 100

mg/L for 72 hours was required to reduce the growth rate of the alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata by 50%.2

- The EC50 of imidacloprid for Daphnia magna was 96.65 mg/L.

However, the EC50 declined to 90.68 mg/L when predator cues

were added to the water as an additional stress. Sublethal exposures

reduced feeding and increased respiration rates in

Daphnia. Exposed Daphnia did not respond to predator cues as

quickly as did control animals, and failed to mature as quickly

or produce as many young. These changes led to reduced population

growth rate following exposure.58 See the text box on EC50.

EC50: The median effective concentration (EC50) may be

reported for sublethal or ambiguously lethal effects. This

measure is used in tests involving species such as aquatic

invertebrates where death may be difficult to determine.

This term is also used if sublethal events are being

monitored.

Newman, M.C.; Unger, M.A. Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology; CRC Press, LLC.: Boca Raton, FL, 2003; p 178.

Terrestrial Invertebrates

- Oral LD50 values for bees range from 3.7 to 40.9 ng per bee, and contact toxicity values ranged from 59.7 to 242.6 ng per

bee.59 Based on these values, imidacloprid is considered to be highly toxic to bees.18 Colonies of bees (Apis mellifera) appeared

to vary in their sensitivity to imidacloprid, perhaps due to differences in oxidative metabolism among colonies. The

5-hydroxyimidacloprid and olefin metabolites were more toxic to honeybees than the parent compound.60

- Bees were offered sugar solution spiked with imidacloprid at nominal concentrations of 1.5, 3.0, 6.0, 12.0, 24.0, 48.0, or 96.0

μg/kg for 14 days. The experiment was repeated with bees that matured in July (summer bees) and between December

and February (winter bees). Summer bees died at greater rates than controls in the 96 μg/kg treatment, whereas winter

bees demonstrated increased mortality at 48 μg/kg. Reflex responses of summer bees decreased at 48 μg/kg, whereas the

reflex responses of winter bees were unaffected. Learning responses in summer bees were decreased following exposures

of 12 μg/kg imidacloprid, and winter bees demonstrated reduced learning responses at doses of 48 μg/kg.61

- Surveys of pollen collected by bees from five locations in France revealed detectable residues of imidacloprid or its metabolite

6-chloronicotinic acid in 69% of the samples. Maximum detected concentrations were 5.7 μg/kg and 9.3 μg/kg for

imidacloprid and the metabolite, respectively.62

- Researchers performed 10-day chronic exposure tests on honeybees and found that mortality increased over controls at

doses as low as 0.1 μg/L of imidacloprid and six metabolites.60

- Researchers fed bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) nectar and pollen spiked with either 10 μg/kg or 25 μg/kg imidacloprid

in syrup and 6 μg/kg or 16 μg/kg in pollen. Worker survival rates declined by 10% in both treatment groups and brood

production was reduced in the low-dose group.63

- Researchers grew sunflowers from seeds treated with 0.7 mg imidacloprid per seed and found imidacloprid residue in

nectar (1.9 ± 1 ppt) and pollen (3.3 ± 1 ppt). No metabolites were found in nectar or pollen. They also grew sunflowers from

untreated seeds in soil with imidacloprid residues at concentrations up to 15.7 ppt. In that test, neither imidacloprid nor its

metabolites were found in nectar or pollen.59

- Researchers have found that bees avoided feeding on a sugar solution spiked with imidacloprid at 24 μg/kg concentrations,

and that this avoidance appeared to be due to a repellent or antifeedant effect.64

- The predatory insect Hippodamia undecimnotata experienced reduced survival, delayed and reduced egg production, reduced

longevity, and reduced population growth rate following exposure to aphids raised on potted bean plants which

had been treated 10 days earlier with imidacloprid applied at 0.0206 mg active ingredient per pot or 1/14 the label rate.65

- Adult green lacewings (Chrysoperla carnea) exhibited reduced survival rates after feeding on the nectar of greenhouse

plants that had been treated with granules of a commercial product containing 1% imidacloprid. Treatments were done

with imidacloprid-containing products mixed at label rates and at twice the label rate three weeks prior to the experiment.

Insects fed on the treated plants even when untreated plants were present.66

- The LC50 for the earthworm Eisenia foetida was determined to be 10.7 mg/kg in dry soil.2 In a separate study, two earthworm

species (Aporrectodea nocturna and Allolobophoria icterica) were placed in soil cores treated with 0.1 or 0.5 mg/kg imidacloprid.

At the highest dose, both species of worms produced shorter burrows. A. nocturna also produced fewer

surface casts at the highest dose, and gas diffusion through the soil cores was reduced by approximately 40% compared

to controls.67

- The reference dose (RfD) is 0.057 mg/kg/day.31 See the text box on Reference Dose (RfD).

Reference Dose (RfD): The RfD is an estimate of the quantity of

chemical that a person could be exposed to every day for the rest

of their life with no appreciable risk of adverse health effects. The

reference dose is typically measured in milligrams (mg) of chemical

per kilogram (kg) of body weight per day.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Integrated Risk Information System, IRIS Glossary, 2009. https://www.epa.gov/iris/iris-glossary#r

- The U.S. EPA has classified imidacloprid into Group E, no evidence of carcinogenicity, based on studies with rats

and mice.20,31 See the text box on Cancer.

- The acute Population Adjusted Dose (aPAD) is 0.14 mg/kg.31

- The chronic Population Adjusted Dose (cPAD) is 0.019 mg/kg/day.31

Date Reviewed: April 2010

Please cite as: Gervais, J. A.; Luukinen, B.; Buhl, K.; Stone, D. 2010. Imidacloprid Technical Fact Sheet; National Pesticide

Information Center, Oregon State University Extension Services. https://npic.orst.edu/factsheets/archive/imidacloprid.html.